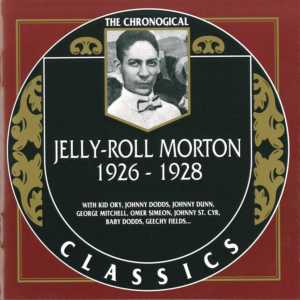

In this blog, I will be surveying jazz from its beginnings right up to the present day. Along the way I will pick out artists of note, and recommend tracks and CDs. Where available, I will link to tracks on YouTube.

If you want to play at home, you might want to get hold of Ted Gioia, (1997),

The History of Jazz, and possibly also Brian Morton & Richard Cook, (2010),

The Penguin Jazz Guide: the History of the Music in the 1001 Best Albums.

See if you agree with my picks and my reasons.

The challenge: beginning our time line

The first problem we have is where to start. It is generally thought that jazz coalesced out of two main streams of African- American music that circulated at the end of the 19th Century/beginning of the 20th Century: ragtime and blues.

|

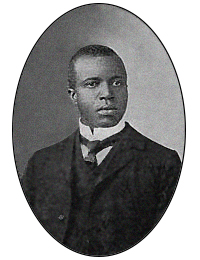

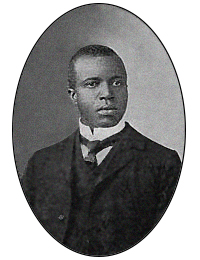

| Scott Joplin |

As ever, things aren’t quite as simple as that. Black pianists like Scott Joplin came to prominence after appearing at the World's Fair in Chicago in 1893, and starting the ragtime craze. However, they didn’t come from nowhere: Joplin (from Texas) says he was trying to imitate, on piano, the banjo style he had heard black musicians play in the plantations of the South; some of his early sheet music carries the instruction, “in the banjo style”. These are the same roots that blues music grew from.

“Rag time” means the music is played in ragged – that is, uneven - time; in other words, it is syncopated. Melody lines are played out of kilter with a steady left hand bass. And we hear the sort of thing Joplin said he was imitating in the early country blues, in players like Mississippi John Hurt. (Though of course by the time Hurt recorded, he would have heard both ragtime and jazz). So, rather than being two separate streams that joined to become jazz, ragtime and blues in some respects are descendants of a common ancestor.

Genre fluidity

However, rather than being separate and fenced off, they seemed to recombine and re-pollinate each other. Classic jazz as we understand it is primarily played by a brass and woodwind front line, and country blues by string ensembles. But in the very early days this seems to have been fluid: there are very early recordings of string ensembles playing music that can be described as proto- jazz. Freddie Keppard, for example, played violin and mandolin before switching to cornet. Early in the history of jazz, violins would sometimes carry the melody in an otherwise brass setting. There was also a change in fashion between tuba and double bass to carry the bass part, which seems to go in the opposite direction of the more general strings to brass shift. And whether the musicians were playing ragtime, what later became known as jazz, or blues seems not to have mattered much to them: for example listen to the early recordings of New Orleans blues guitarist Lonnie Johnson to hear the way string ensembles of violin, mandolin, guitar could play jazz or blues.

The era of sound recordings

The next problem we have is that the very first jazz music was never recorded. It was played by black performers, often for black audiences. Those very early audiences didn’t have the money to buy records, and it didn’t occur to the record producers to record it. (Not, that is, until later, when white audiences – with the cash to buy records – got interested in jazz). Thus Buddy Bolden, regarded by musicians such as Louis Armstrong, Bunk Johnson, and Jelly Roll Morton as at least being important in the foundation of jazz, and by some as being the progenitor, was never recorded. (There is a legend that he may have made a recording on a paper disc, or cylinder, but it has never surfaced).

|

| Buddy Bolden |

Bolden, an alcoholic, was diagnosed with dementia praecox and committed to an asylum in 1907, never to return to the music scene. None of his contemporaries was recorded until over a decade later - some considerably later than that - by which time fashions in jazz had moved on, and we can’t know whether those players had been influenced by later trends and modified their own styles through time. Bolden’s most famous tune was “Funky Butt”; see Humphrey Littleton’s reconstruction here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x5tZcwmw8M4

When jazz became widely popular in the so-called Jazz Age of the 1920s, those very early artists were still around. But nobody then thought to seek them out and ask them about their experiences, or what they sounded like in the beginning. For one thing jazz was all about the next innovation, not the out-of-date sounds of yesteryear, and for another thing, those were poor, provincial blacks. Oral historians weren’t much interested in them at the time.

Acoustical recording

The other distorting fact we have is the recording process itself. In very early recording, sound was collected mechanically rather than electronically. Musicians played into a horn rather than microphones. (

Acoustical recording). This method was not good at reproducing drums, pianos, or even plucked double bass. Often jazz bands were recorded without those instruments, or with drummers and pianists asked to tone down or modify what they played. This was bound to have a knock-on effect on the way other instruments played. Without the bass or drum part you are used to, you will not be propelled to play the way you normally play.

|

| Acoustical recording |

Even in the early electrical era, the reproduction of sounds was poor. (We’ll never know how Bix Beiderbecke sounded in the flesh). It was much worse in the acoustical era.

Also, playing time was restricted by what would fit on one side of a disc. There were no LPs until decades later! Add to that the unfamiliar environment, the fact that recording technicians often interfered by telling musicians how to play, and the fact that some bands – ironically concerned with posterity – didn’t improvise as freely in recording sessions as they would in a dance hall (Jelly Roll Morton, for example, more or less dictated the parts his recording bands should play), and you get the picture of a music ill-served by the early technology and recording industry.

What’s in a name?

Books are often fairly coy about where the word “jazz” comes from; perhaps unsurprisingly, as it seems to have been a term for male sexual juices, which then became slang for doing something with vigour (similar to the word “spunk”). It doesn’t seem to be used as a term for a music genre until around 1915, although prior to that musicians may have talked of jazzing their performance up, meaning giving more oomph and wow to the proceedings. Many of the early exponents of the music seem to have gone on preferring to call the music they played “ragtime”, even though “ragtime” no long accurately described what they did, and even long after the term jazz gained public acceptance in describing the genre. Buddy Bolden, it is almost certain, never called his music “jazz”. Even Kid Ory went on talking of ragtime long into the 20s.

So what are the attributes of jazz? In the very early part of the 20th Century, it was syncopated music, featuring African-descended polyrhythmic ideas, and African tonality, specifically

blue notes on the 3rd and 7th of the scale, and some degree of improvisation. And most of all, it swung.

The musicians playing it had imbibed ideas from European music, from the folk music of neighbouring poor whites, from the Caribbean, and some element of Latin dance music that Jelly Roll Morton called the “Spanish Tinge”. New Orleans was a cauldron of cultures and music, and jazz was neither African nor European, but American.

Choosing a starting point

The first band calling itself a jazz band to make a record was a white band. They were called the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Their first release was “Livery Stable Blues”. However, their sound is not typical of early jazz, and their music – especially this first record – was novelty music, which seems to find cheap humour in black music in a way somewhat akin to

minstrelsy. It lacks a deep passion and understanding, and is played for laughs. (My dubiety towards the sincerity is only amplified by leader Nick LaRocca’s overt racism in his later self-promoting writing). Their records also contained little by the way of improvisation: each chorus is played much the same way as the last.

Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke were among those who rated them, and some of their tunes – such as Tiger Rag – became standards in the hands of others, but looking back I don’t hear what they heard. They have a certain charm taken on their own terms, and were hugely popular and had an enormous effect on the popularization of jazz music, but I don’t think they are representative of jazz of the time. I’m not choosing the ODJB as a starting point; they weren’t the beginning, they only got into the studio first.

Instead, I’m opting for

Freddie Keppard.

Find out why soon...

Suggested reading: Gioia, T, (1997),

The History of Jazz. Chapters 1 & 2.

Shipton, A, (2007),

A New History of Jazz, Revised and Updated Edition. Chapter 1.